Directing : Pentlands at War

contd

I had decided at an early stage that I wanted to maximise the dramatic potential of our village hall as a theatre space. The Victoria Theatre in Stoke-on-Trent is a theatre in-the-round: i.e. the audience is seated all around the stage. This is a wonderfully democratic form of theatre – every seat is as good as the next, and the circular shape brings a genuine communality to the event. Carlops Village Hall has no conventional stage. It is a long rectangular empty space. I decided that we would perform our Pentlands At War play in traverse, i.e. the audience would sit on both long sides of the rectangle, facing one another, not quite theatre-in-the-round, but a close relation. The full length of the hall itself would be the stage. We would have a structure of stepped rostra at one end, which could be used by the singer in the band, and could give us another smaller, but higher, playing area.

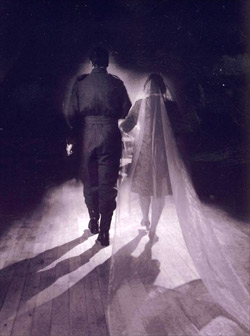

This decision definitely gave a dynamic to our writing – we knew we were writing for this long rectangular playing space, which offered us the possibility of, for example, riding a bicycle right along the stage from one end of the hall to the other, of creating a jungle river, and of using a long clothes line skipping rope, as children used to do in the school playground, for communal skipping. Because the hall itself was the stage, 'The Dance in the Village Hall' scene literally became that – the actors danced on the floor of our village hall, with the audience sitting round them as many people do at a village dance. The rostra structure became the bus, the ship, the aeroplane, the army truck, the banks of the River Lyne, and Mary's window (an echo of Romeo and Juliet's balcony scene).

I listened to music from the period, and discussed with our splendid musical director Murray Campbell, the rhythmic, melodic and harmonic threads which might help to tie together the many stories and thematic strands of the script. Murray composed a beautiful, subtle score, drawing on war-time band music, and cleverly blending traditional Scottish elements, with an Italian theme. Stuart Delves discovered, through the Imperial War Museum, the words of a song written in Rangoon prison by John Wild, one of our interviewees. Murray composed an evocative melody for John's words, and arranged the song for the band with a thrillingly theatrical tom-tom jungle beat. Murray's score, interwoven with the sound effects of wild geese, seagulls, trains, bomber planes, etc helped to create a dynamic theatrical style for the production.

It was agreed that I would put together a first draft of our two-act play, and that the five writers would spend a day round a table reading this draft aloud, commenting on it, and then restructuring the script if necessary. Inevitably, some scenes were cut altogether, and some were trimmed. And, a little to our surprise, at no point did we fall out over the process! We all seemed to understand that this play belonged more to the community than to us as individual writers. I think that the particular nature of the project probably informed our way of working; our first responsibility was to the endeavour, and not to our own fragile creative egos.

Once we had a working script, the auditions began. 34 magnificent local talents signed up for acting, singing and dancing, and Murray mustered a bunch of superb local musicians - Glen Miller eat your heart out! We rehearsed most evenings and every weekend over a couple of months. Our wonderful costume designer, Rachel Ntuli, ran props-making workshops for local children, who produced the gas-masks worn by the evacuees in the play, and the dazzling sequinned fish which exploded into the auditorium when the grenade was thrown into the River Lyne!

Our professional production team also included a production manager (Sally Charlton deserves a military medal for co-ordinating the nightmarishly complex logistics of cast availability for rehearsals!), lighting designer, choreographer, publicist and sound technicians, and we hired the necessary authentic army uniforms from the unstintingly helpful costume hire company Flame Torbay. The combination of amateur performers and professional production team worked with tremendous efficiency and passionate commitment.

We gave four performances of our play between Christmas and Hogmanay to packed audiences. Everyone involved in the project forged many new friendships, and renewed old acquaintances. It was a privilege indeed to observe my old school janitor (who will be 90 on his next birthday), watching his own wartime story being told. A remarkable man, he got through the war physically in one piece; emotionally and psychologically shredded by the experience, he subsequently devoted his life to working with young people. Pentlands At War gave us the chance to learn from and give something back to those - some still in our midst - who gave themselves to our community.

As a record of our endeavours, I have produced the full script of Pentlands At War, as we performed it, complete with stage directions, and notes on sound effects, movement, music and lighting. Like memory itself, the very nature of theatre is ephemeral: we can never truly recapture the moment in time that brought us together. But that's the beauty of it – the creation of a collective memory.

Gerda Stevenson, Director of PENTLANDS AT WAR, May 2006.

The first performance of PENTLANDS AT WAR was given in Carlops Village Hall,

29th December, 2005.